By Diego Sandoval (he/him) Youth v. Oil Media Lead

Unbeknownst to many, San Diego finds itself more racially segregated now than it was 30 years ago. This City has its roots in native and Hispanic heritage, yet, those same communities find themselves systematically disadvantaged in the present. San Diego as we know it was established by the Spanish in 1769 with the creation of Mission San Diego de Alcala. The descendants of these Spanish, the Californio Rancheros, played a vital role in the community, alongside Mexicans who gained independence from Spain in 1821. Before Europeans arrived, natives had been living in San Diego as early as 20,000 years ago; at the time of the first contact with the Spaniards, there was a population of 19-25 thousand Kumeyaay, a native tribe, living in San Diego. Conflict and diseases exchanged between the Natives and the Spanish devastated Native populations in a relatively short amount of time.

Following the ratification of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848, which ceded to the US Mexican territory that includes much of the modern western states, and coinciding with an increase in immigration from the East caused by the California Gold Rush, many Mexican Americans chose to vacate, while those staying faced discrimination and political marginalization due to being outnumbered. This marked a crucial turning point in San Diego’s history, as Mexican-Americans no longer held political power. This disparity was heightened as San Diego’s population skyrocketed during the 1880s with immigrants following the construction of the California Southern Railroad.

WWII served as another turning point in Chicano history as war industries provided immense employment opportunities in San Diego for Hispanics, contributing to this, the Bracero Program brought Mexicans to work in the US, including San Diego, to serve as temporary contract workers- many seeking paths to become Permanent Residents. The war effort had brought much activity to San Diego’s shores, this combined with the growing societal need for cargo ships led to the birth of modern Shipyards in San Diego during the 60s alongside the establishment of the port in 1962 to manage the surrounding water. The shipbuilding company, General Dynamics NASSCO, provided immense employment opportunities for Mexican-American San Diegans, especially throughout the 70s and 80s when it saw a boom in activity. Shipbuilding and retrofitting efforts concentrated alongside communities made up of predominantly Mexican and Asian Americans with historically low Median Household Incomes. These communities, most notably Barrio Logan, National City, and Chula Vista, served as great portions of NASSCO’s workforce.

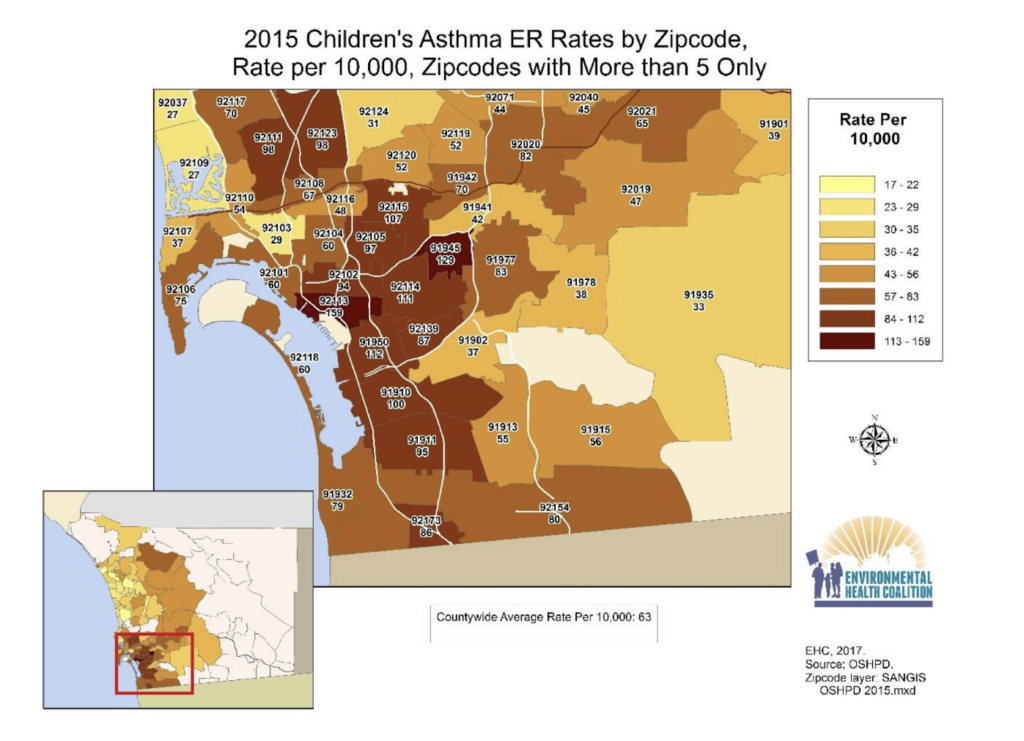

The same employers responsible for giving these communities employment were simultaneously responsible for polluting the air they breathed. Processes required during shipbuilding, including welding, coating, and use of hull materials are known to emit harmful air emissions. Neighboring industries such as repair shops, manufacturing, and former fuel-processing biodiesel plants are also responsible for a considerable amount of GHG emissions. Proximity to San Diego’s Naval Base, responsible for 40,000 cars coming in and out of it daily, as well as the creation of the I-5 Freeway which divided Barrio Logan and Logan Heights, while also displacing community members, and the creation of the on-ramp to the Coronado Bridge all contribute to the immense diesel pollution these communities are facing. These factors contribute to childhood asthma rates in these neighborhoods being 2.5 times higher than the region’s average, and cancer rates being 85%-95% higher than the rest of the US.

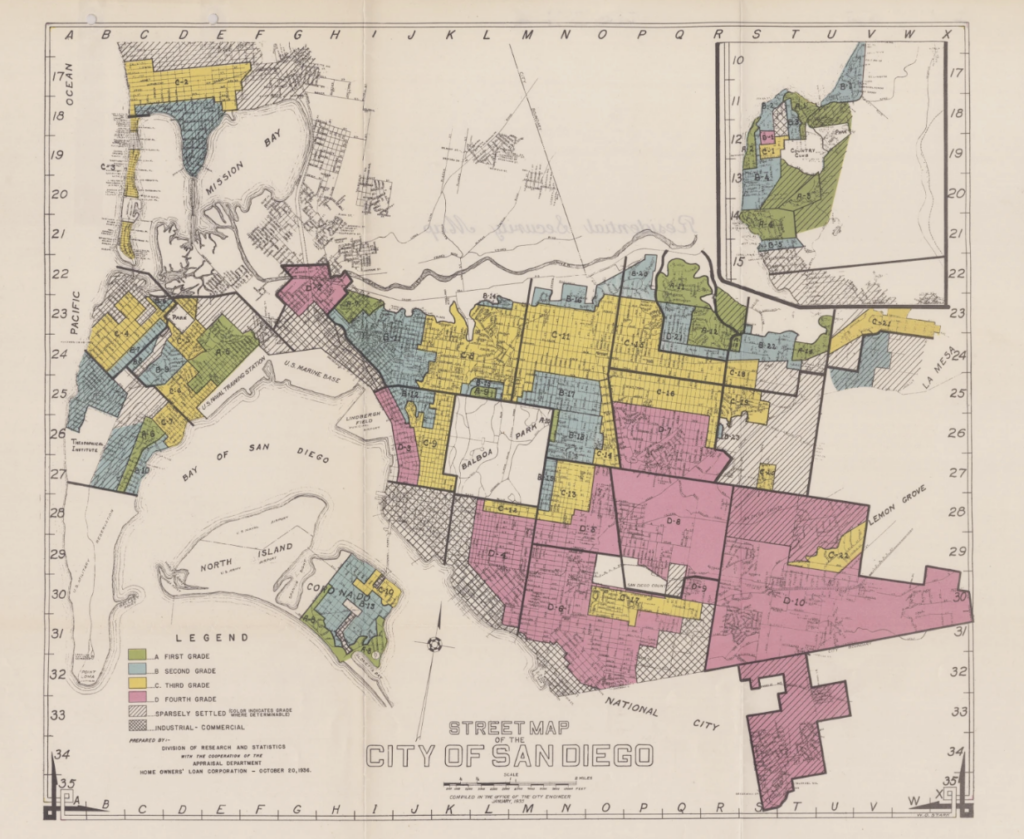

The communities disproportionately affected by pollution are overwhelmingly Hispanic, with Barrio Logan having a population made up of 85% Hispanic or Latino. Additionally, these communities suffer from lower Median household Incomes; this is the result of decades of redlining practices during the beginning of the 20th century and racially restrictive covenants that were present in every San Diegan home through to 1950, which made it impossible for Black, Latino, Asian, and Jewish Americans to purchase homes in many regions of the city. We see the modern-day version of this with single-family zoning, taking up 81% of residential land in San Diego. It has steered lower-income residents away from these notoriously wealthier and whiter neighborhoods into restricted regions zoned for multi-family housing, which often see less investment, access to resources such as good schools, healthy food choices, and access to green spaces. These poorly maintained suburbs are particularly vulnerable to the Urban Heat Island Effect, which we see resulting in higher temperatures in West Chula Vista, National City, and Barrio Logan among others, contributing to higher demand for air conditioning, as well as risk for heat-related injuries.

Many communities that were once labeled as poor financial investments at the height of US redlining, are now considered communities of concern with low climate equity index scores, meaning they are more likely to face environmental, mobility, health, and socioeconomic difficulties. This is not a coincidence! These communities filled with primarily BIPOC families are being forced onto the frontlines of the devastating effects of natural disasters and environmental hazards by the same entities that denied them social, political, and economic power for centuries.

Despite all the odds stacked against them, these communities have refused to stand by while their neighborhoods get polluted. As a result of fearless grassroots advocacy, projects such as San Diego’s Urban Forestation and truck electrification efforts to reduce GHG emissions at the port are being implemented to reduce the disparities faced by these communities. Yet these barely scratch the surface of reconciling the harm that pollution, lack of access to resources, and environmental hazards has caused for decades. This is why it is so important to recognize the struggles and contributions BIPOC communities have made to our great nation on days like today, Juneteenth, because too often we see people discounting efforts to combat injustice as unnecessary or “special treatment.” But the truth is, our society has been intentionally built to propagate the success of certain people and the suffering of others. Only through conscious efforts to empower the communities that have been overlooked and ignored for all of history can we start to right the wrongs of the past and build a better future for all.